- Home

- Catherine Noske

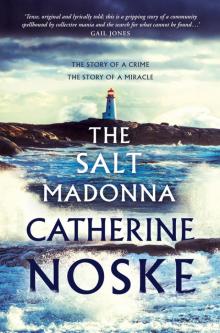

The Salt Madonna

The Salt Madonna Read online

About The Salt Madonna

‘Tense, original and lyrically told; this is a gripping story of a community spellbound by collective mania and the search for what cannot be found...’ Gail Jones

This is the story of a crime.

This is the story of a miracle.

There are two stories here.

Hannah Mulvey left her island home as a teenager. But her stubborn, defiant mother is dying, and now Hannah has returned to Chesil, taking up a teaching post at the tiny schoolhouse, doing what she can in the long days of this final year.

But though Hannah cannot pinpoint exactly when it begins, something threatens her small community. A girl disappears entirely from class. Odd reports and rumours reach her through her young charges. People mutter on street corners, the church bell tolls through the night and the island’s women gather at strange hours...And then the miracles begin.

A page-turning, thought-provoking portrayal of a remote community caught up in a collective moment of madness, of good intentions turned terribly awry. A blistering examination of truth and power, and how we might tell one from the other.

‘Catherine Noske’s The Salt Madonna is Australian Gothic at its most sublime and uncanny. Superbly atmospheric and darkly unsettling, the characters are haunted by their colonial pasts, manifested in guilty silence . . . Noske’s taut, subversive writing exposes unspeakable truths buried in dazzling stories, miracles and epiphanies.’ Cassandra Atherton

Contents

Cover

About The Salt Madonna

Dedication

Acknowledgement of Country

Epigraph

Excerpts from Terra Ignota: Exploration in Australia’s South

Preface

Chapter I: December 1991

Chapter II: January 1992

Chapter II: January 1992

Chapter IV: February 1992

Chapter V: February–March 1992

Chapter VI: March 1992

Chapter VII: April 1992

Chapter VIII: April–May 1992

Chapter IX: May 1992

Chapter X: June 1992

Chapter XI: June 1992

Chapter XII: July 1992

Chapter XIII: August 1992

Chapter XIV: September 1992

Chapter XV: September 1992

Chapter XVI: October 1992

Chapter XVII: October 1992

Chapter: XVIII

Acknowledgments

About Catherine Noske

Copyright page

For my family and for Lucas, with my gratitude and love.

I WOULD LIKE TO acknowledge the sovereignty of Australia’s First Nations peoples, and the importance and vitality of their cultures. I need to recognise in particular the traditional owners of the lands on which I lived and loved while writing this.

I acknowledge the Cart Gunditj Clan, Gunditjmara Nation in the Dhauwurd Wurrung Language group upon Pinnumbul (Mt Clay), where part of this book was written.

I recognise the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations, where I lived when writing the first drafts of this work.

And finally, I acknowledge the Whadjuk Noongar people, sovereign owners of the land on which I currently live and write.

I pay my respects to the Ancestors of these ancient lands, their elders past and present as well as the members of the present day communities.

I thank them all for their custodianship of these Countries.

I wish this story were different. I wish it were more civilised. I wish it showed me in a different light, if not happier, then at least more active, less hesitant, less distracted by trivia. I wish it had more shape [ . . . ] I’m sorry there is so much pain in this story. I’m sorry it is in fragments, like a body caught in crossfire or pulled apart by force. But there is nothing I can do to change it.

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

12 March 1829

Wind WNW, 18˚C

3 seen today by the inland Swamp. The testing has brought nothing, still. We will have to leave soon. Supplies are running short. I don’t suppose W. is fool enough to let us starve. We have named the island Chesil, for the Isle of Wey Portland, which W. claims it resembles in shape, though it would be impossible to tell, and there is no shingle to join it in any way to the Mainland. [ . . . ] clay and sand and no good Soil for growing.

‘Journal of John Granville Mulvey’, as transcribed in Robert Fauxman, Terra Ignota: Exploration in Australia’s South, 2007, p.123

Another such example is the diary of John Granville Mulvey, written during his years of service from February 1828 until October 1829. This was very much a period of exploration along the south coast, as the land of various regions was considered for the expansion of farming. While not much is known of Mulvey himself – his use of language proves he was well educated, although various entries suggest he was potentially a convict – the exploratory party of which he was a member, as described in the last year of his journal, was unique. Led by young Lieutenant James William Wakefield, the party was commissioned by a British noble, possibly Lord William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, Marquess of Titchfield and fifth Duke of Portland. Mulvey describes in great detail various landings all along the south coast, from Albany in Western Australia to what would later become the Portland Bay settlement of the Henty family in Victoria.

[ . . . ] The landing made on Chesil Island proved auspicious for Mulvey, as he later returned and took land as a pioneer farmer, effectively founding a settlement there. Mulvey’s descendants still have possession of the original run, and continued to live on the island into the 1990s.

Robert Fauxman, Terra Ignota: Exploration in Australia’s South, 2007, pp.123–4

TODAY, I MET A GIRL who looked like Mary. Dark eyes, light hair. She sat at the back of my classroom like Mary used to, and said nothing. She watched me, though. Dark eyes. And now I cannot sleep.

A story: Once upon a time, or a long time ago, a man called Mulvey started a settlement on an island called Chesil. He got rich hunting the whales, until they disappeared. He dragged pasture out of undergrowth and stole the pasture created by others, fouled the water, ringed trees with deep scars and cleared them. He brought sheep and they died. He brought cattle and they survived. He lived there and he died there, and his children lived and died there, and their children, and so on until I was born. I lived there and then I left. I used to tell myself that it was my mother who made me leave. She stood on the ferry dock as the boat pulled out, but she didn’t wave. She just stood there, and held me with her eyes, until suddenly I couldn’t see her anymore and I was gone.

Once upon a time, a girl called Mary lived on an island called Chesil.

Once upon a time, my mother was dying and I went home.

It is beautiful, Chesil. It looks impossible from the mainland; it floats disembodied on the horizon. It grows into its own reality as you get closer across the bay, assuming a depth and solidity that is unexpected. The ferry churns through cross-current, and the fine detail starts to unfold. Cliff faces take on shadows, trees emerge on the hill. As you round the point, a statue of the Virgin welcomes you, watching over the bay, arms spread benevolently, blue robes faded and splintered by salt. The beach spreads itself in gold and grey. The rail bridge appears to the west, stretching back towards the mainland, tethering the island to the real world. The bridge was built to take the grapes out, but it is abandoned now, left to bleach silver in the sun. Gap-toothed boards curl up from the lattice of the sleepers beneath. When the wind is from the east, it sings.

Reaching the island becomes a possibility the moment you see the bridge. The ferry from one point, the bridge from the other, they reach like arms to hold the island in, keep it connected. The layers

of the place – beach, village, vines and bush – stand as bands of colour framed by sky and sea. The symmetry is almost overwhelming.

You cannot see my home from the ferry, but I can place it. Up from the church, over the shoulder of the hill, swaddled and hidden in folds of the forest. The hill is the only place still left as bush. It is a backdrop, coming in. The deep notes in a painting, the measured counterbalance to the weight of the sea.

You see the people last. It is strange the way they appear – they seem less real than the place itself. When I went back, Darcy was down there waiting for me, standing on the ferry dock where my mother had seen me off. He had his hat pulled so far down his brow that I couldn’t make out his face. I was expecting my mother. It hadn’t occurred to me that he might come.

The island floats disembodied. They aren’t my words. I took them from a diary. The man who wrote them, my ancestor, seemed to appreciate – even in the midst of all that unknown world – that the island was somehow apart. My family shaped this place, cut it open. From one of its trees, my ancestor carved the Virgin and left her standing rough-hewn on the point to watch over those entering the bay. Arriving. We Mulveys have always counted time from moments of arrival. In his diary, that first Mulvey talks about beginning this place, starting it. The world of the island’s inhabitants was not real to him. They existed in some other way, they were ghosts, some malevolent manifestation of the place itself. Such a convenient notion. Indigenes, sprung from the land. Autochthony not wondrous or beautiful, but to him a dangerous force.

I’m feeling quite light-headed. It might be good for me, writing about the island. Even the word, Chesil. I miss it. I need it. I can’t say why. It is the marker by which I know my world, a touchstone, it is magnetic north. Something has come in under my fingernails and changed me. Perhaps. Perhaps I am in mourning for a place and a life that was never real, only a child’s make-believe. It felt like that, when I went back. My memories were a transparency laid over the day-to-day. At moments the two versions aligned, and I could forget which one I was living. I went home only a week after we heard our mother’s diagnosis. Sophie, my sister, arranged it all: found me the position at the school on the island, lined everything up and presented it fait accompli. Expected me to carry the burden for both of us. Made it clear I had no choice. It wasn’t like I had anything to keep me from going. There was nothing in my life then for me to miss. Not that she put it like that – we didn’t talk about it much. She felt guilty, I think, that with her husband’s job, her children’s school, she couldn’t come. Perhaps too, for her as well, the island was a private fantasy world separate from mundane life. It isn’t her failing that we didn’t talk. I could have spoken more: to her, to Darcy, to my mother. It was my fault. I should have tried harder. My uncle cried at my mother’s funeral. I’d never seen him as anything but a name until then. It’s so easy to forget that everyone will have their own story.

But some of that child-world was real, I think. I still ride, at a stable now, dressage, I dance – classical training on someone else’s horse. Lateral work is a challenge. It is the movement of the horse’s shoulder. When I feel it swing from me across the arena, I am a child back on Chesil, on my bay pony and galloping like we used to along those winding trails, following the horse, out of the saddle and guided by his weight. Every time I feel that shoulder move, some part of me leans forward, stands up. It is just the tiniest shift but instantly the dance is ruined, the horse will stumble, all because I cannot get that place out of my mind. My instructor cannot understand it. I am not even aware I am doing it half the time. You wouldn’t see it, it is nothing more than a twitch, a reflex reaction. Still, it will ruin me as a dressage rider.

Darcy taught us to ride like that, leaning forward. Toes thrust well through the stirrup, heels heavy and stretching down. Hands forward, body forward, reins bridged. Go with his shoulder. Sit with him, not against him. My straitlaced instructor has no idea.

I followed the Royal Commission, while it happened, the stories, the thousands of stories coming out about abuse, and assault, and trauma, and shame. I watched one of the public sessions. They were streaming it online. I could not bring myself to register – to follow the links, the invitations to tell my story. I don’t think mine was the type of story they wanted to hear. I didn’t think I could tell it. But I saw them. There were only three of the Commissioners present: old, white men, sitting, contemplating, uncomfortable in their efforts to demonstrate empathy in listening. What could they really understand of any of it? How could anyone empathise? The camera did not move, held the shot, framed them as a horizon across the screen.

They released figures after it was all finished: 8000 private sessions, 42,000 calls handled. That phrase – handled – made me uncomfortable. (What had been handled?) It all seemed to imply that something was finished. The final statistic was perhaps the most frightening: 2575 referrals, including to the police. I went cold, reading that. Two and a half thousand people with a legitimate case for justice, and no prior action. I remembered my own call to the police. Justice, I thought. A story passed on, and so finished. Hands dusted. It made me feel sick.

I was not the only one. I am teaching again, here in the city. It has taken me a while, but I am at a small school, with a nice group of colleagues. We all followed the hearings, the gossip around it, the schools that had been exposed. It was, of course, after all, not the abuse that mattered, but the Institutional Response. The chatter in staffrooms all across the country took it up, talking about assault and trauma in clichés, over cups of tea and cheap biscuits. Under it all, you could almost hear the refrain, not us, thank God, not us. In one meeting, we were given the Preliminary Report to consider and reflect. Reading it, I couldn’t work out how they could ever go forward with it. How could you draw a line? How could you decide which stories to follow, which case studies to raise? How could you live with that? At the school, we spoke in the meeting about a ‘history of violence’, the repression of trauma erupting in daily behaviour. But this whole country has a history of violence. It is everywhere. Like Mary. (Can you sense me struggling to say her name?) We won’t ever deal with it openly. The only possibility we have is to pass it on.

When I saw Mary sitting at the back of my classroom again, I felt it turn. Some things will always come back; there are stories that will never be resolved.

I can’t tell you everything, but maybe I can piece together enough – about them, there on Chesil: my mother and Darcy, Mary and Thomas, Father John, my uncle, even. And me, I know my own fault in this. There are things I didn’t see, of course. Things I can only imagine. Perhaps there is a reality in imagining. I could argue the Aristotelian principle: art is truth unrestrained by the incidentals on which history is dependent. Besides, I might be the only one left who can tell it.

There are two stories, really. Once upon a time, a girl called Mary lived in a village on an island called Chesil. Once upon a time, I went home.

I

December 1991

The Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, 8 December

Christmas Day, 25 December

Saint’s Day of Stephen, first Martyr, 26 December

Saint’s Day of John, Apostle and Evangelist, 27 December

Saints’ Day of the Holy Innocents, 28 December

THE DARK MAN LEANS against the rail to watch the ferry come in around the point. There is only one passenger, one car. He waves at a fly and pulls his hat further down his brow. Behind him, the shed door opens. A younger man emerges and meanders down the jetty.

‘Darce,’ the ferryman says.

‘Frank,’ Darcy replies.

The ferry grinds its way along the jetty. The passenger is standing on the deck, one hand raised to shield her eyes from the brilliance of the day. Darcy stands up straighter, steps forward. He can tell when she sees him – she snaps tight, her whole body at attention. He grins. Steady, child, he thinks.

*

This is how I will do it. This is

how I will imagine. Darcy there, I saw him pull his hat down. So I know it is the truth. That gesture, I’ve seen him do that a million times. But a story like this can’t be told from one set of eyes. There are too many things you have to see. This is how it will have to happen – I will show you all of us. They will forgive me. Of everything, they will forgive me this.

Do you recognise me yet? Let me start again.

*

Darcy leans against the rail to watch the ferry come in, around the point and under the Virgin’s shadow. There is only one passenger, one car. The car is a garish green, unnatural against the deeper colour of the water. He waves at a fly and pulls his hat further down his brow. Behind him, the shed door opens and a younger man emerges, pulling the ferry company’s t-shirt on over a torn pair of jeans as he meanders down the jetty.

‘Darce,’ the ferryman says.

‘Frank,’ Darcy replies.

The ferry grinds its way along the jetty, its engines grasping and tearing at the water. The passenger is standing on the deck, one hand raised to shield her eyes from the brilliance of the day. Darcy stands up straighter, steps forward. He can tell when she sees him – she snaps tight, her whole body at attention. He grins. Steady, child, he thinks.

The ramp comes down and the man at the controls yells. As Frank moves forward to get the chain, she slips into the driver’s seat and starts the engine. Her car judders down the ramp, suspension soft over the lip of the jetty, and she steers it all the way clear, past him and up to the car park at the top. The car door is flung open and she bursts out, comes flying back down the jetty towards him. He is grinning, so hard his face hurts. When he holds his arms open, she hesitates only a moment before she hugs him.

‘Hey, kiddo,’ he says, muffled into her shoulder.

She just laughs. ‘I thought Mum would come,’ she says as she pulls away.

The Salt Madonna

The Salt Madonna